Judgments based on intuition seem mysterious because intuition doesn't involve explicit knowledge. It doesn't involve declarative knowledge about facts. Therefore, we can't explicitly trace the origins of our intuitive judgments. They come from other parts of our knowing. They come from our tacit knowledge and so they feel magical. Intuitions sometimes feel like we have ESP, but it isn't magical, it's really a consequence of the experience we've built up.

INTRODUCTION

By Daniel Kahneman

We are prone to think of the British as snobbish, a label that is rarely used to describe Americans. When it comes to the adjective "applied," however, the tables are turned. The word "applied" does not have any pejorative or diminishing connotation in Britain. Indeed, the Applied Psychology Unit on 15 Chaucer Road in Cambridge was for decades the leading source of new knowledge and new ideas in cognitive psychology. The members of that Unit did not see their applied work as a tax they had to pay to fund their true research. Their interest in the real world and in theory merged seamlessly, and the approach was enormously productive of contributions to both theory and practical applications.

In the US, the word "applied" tends to diminish anything academic it touches. Add the word to the name of any academic discipline, from mathematics and statistics to psychology, and you find lowered status. The attitude changed briefly during World War II, when the best academic psychologists rolled up their sleeves to contribute to the war effort. I believe it was not an accident that the 15 years following the war were among the most productive in the history of the discipline. Old methods were discarded, old methodological taboos were dropped, and common sense prevailed over stale theoretical disputes. However, the word "applied" did not retain its positive aura for very long. It is a pity.

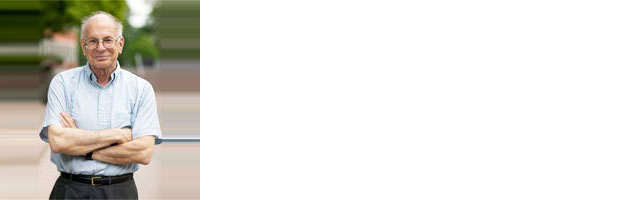

Gary Klein is a living example of how useful applied psychology can be when it is done well. Klein is first and mainly a keen observer. He looks at people who are good at their job as they exercise their skills, sometimes in life-and-death situations, and he reports what he sees in clear and eloquent prose. When you read his descriptions of real experts at work, you feel that it is the job of theorists to accommodate what he has seen – instead of doing what we often do, which is to scan the "real world" (when we think of it at all) for illustrations of our theoretical notions. Many of us in cognitive and social psychology are engaged in the important exercise that Lee Ross has wonderfully described as "bottling phenomena" and our theories are built to fit what we bottle. Klein himself is a theorist as well as an observer, but his theoretical ideas start from what he does for a living: they are intended to describe and explain a large chunk of behavior in a context that matters. It is instructive to note which of the concepts that are current in academic psychology turn out to be useful to him.

Klein and I disagree on many things. In particular, I believe he is somewhat biased in favor of raw intuition, and he dislikes the very word "bias." But I am convinced that there should be more psychologists like him, and that the art and science of observing behavior should have a larger place in our thinking and in our curricula than it does at present.

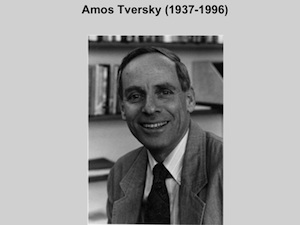

— Daniel Kahneman

GARY KLEIN is a research psychologist famous for his work in pioneering the field of naturalistic decision making. Among his books are Sources of Power and Intuition.

DANIEL KAHNEMAN, Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology, Princeton University, is recipient of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics. He is the author of Thinking Fast and Slow.

INSIGHT

[GARY KLEIN:] What's the tradeoff between people using their experience (people using the knowledge they've gained, and the expertise that they've developed), versus being able to just follow steps and procedures?

We know from the literature that people sometimes make mistakes. A lot of organizations are worried about mistakes, and try to cut down on errors by introducing checklists, introducing procedures, and those are extremely valuable. I don't want to fly in an airplane with pilots who have forgot their checklists, and don't have any ways of going through formal procedures for getting the planes started, and handling malfunctions, standard malfunctions. Those procedures are extremely valuable, and I don't doubt any of that. The issue is how does that blend in with expertise? How do people make the tradeoffs when they start to become experts? And does it have to be one or the other? Do people either have to just follow procedures, or do they have to abandon all procedures and use their knowledge and their intuition? I'm asking whether it has to be a duality. I'm hoping that it doesn't and this gets us into the work on system one and system two thinking.

System one is really about intuition, people using the expertise and the experience they've gained. System two is a way of monitoring things, and we need both of those, and we need to blend them, and so it bothers me to see controversies about which is the right one, or are people fundamentally irrational, and therefore they can't be trusted? Obviously system one is marvelous. Danny Kahneman has put it this way, "system one is marvelous, intuition is marvelous but flawed." And system two isn't the replacement for our intuition and for our experience, it's a way of making sure we don't get ourselves in trouble.