The way nature is—the nature of flowers, the nature of birdsong and bird plumages—implies that subjective experiences are fundamentally important in biology. That the world looks the way it does and is the way it is because of their vital importance as sources of selection in organic diversity, and as a result we need to structure evolutionary biology to recognize the aesthetic, recognize the subjective experience.

~~

...ducks are one of the few birds that still have a penis. It's a very weird structure. It has an explosive erection, its erection mechanisms are lymphatic instead of vascular, it's stored outside-in inside the cloaca and comes flying out, and they can get very lengthy—up to 40 centimeters, which is over a foot long on a duck that is itself not even a foot long. It's an extraordinary piece of biology. What's going on in these ducks?

In lots of ducks there's forced copulation. It's the equivalent of rape in ducks. In species where there is a lot of forced copulation, females have evolved or co-evolved complex vaginal morphologies that frustrate the intromission or frustrate entry of the penis during forced copulation. For example, the penis of ducks is counter-clockwise coiled and often has ridges or even teeth-like structures on the outside. In this case, in these species, the female has evolved a vagina that has dead end cul-de-sacs, so that if the penis goes down the wrong direction it’ll get bottled up and doesn’t perceive to be closer to the oviduct, or further up the oviduct and closer to ova. And then above the cul-de-sacs, the duck vagina has clockwise coils, so there's literally anti-screw devices that prevent intromission during forced copulation.

(1 hour)

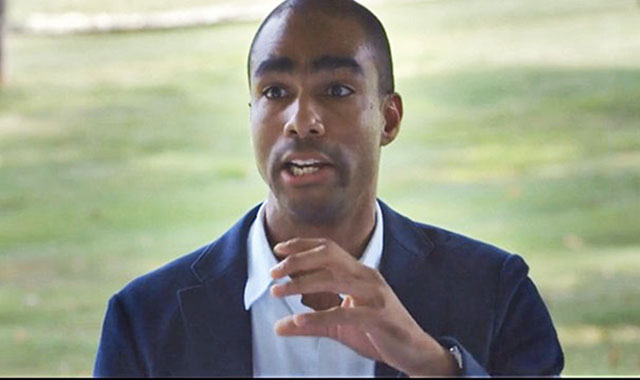

RICHARD PRUM is an evolutionary ornithologist at Yale University, where he is the Curator of Ornithology and Head Curator of Vertebrate Zoology in the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. Richard Prum's Edge Bio Page

DUCK SEX, AESTHETIC EVOLUTION, AND THE ORIGIN OF BEAUTY

Over the last few years I've realized that a large portion of the work that I've been doing on bird color, on birdsong, on the evolution of display behavior, is really about one fundamental and important topic, and that's beauty—the role of beauty in nature and how it evolves. The question I'm asking myself a lot now is: what is beauty and how does it evolve? What are the consequences of beauty and its existence in nature?

There's a long history of people thinking about ornament in nature—those aspects of the body or the behavior of organisms that are attractive, which function in perception of other organisms. Usually we think about this in terms of sexual selection or mate choice, but there's a bunch of other contexts in which it can occur, like flowers attracting pollinators and fruits attracting frugivores, or even the opposite—a rattlesnake or a poisonous butterfly scaring away predators. These are all aspects of the body that function not in the regular way but in perception.