NEW — A Reality Club discussion with responses from: Abbas Raza, William Poundstone, Hugo Mercier, Quentin Hardy, Martin Nowak and Roger Highfield, Bruce Schneier, Kai Krause, Sumit Paul-Choudhury, Margaret Levi.

That is basically what interests me—the double question of understanding our own biases, but also understanding the potential of using this indirect information and these indirect cues of quality of reputation in order to navigate this enormous amount of knowledge. What is interesting about the Internet, and especially about the Web, is that the Internet is not only an enormous reservoir of information, it is a reputational device. It means that it accumulates tons of evaluations of other people, so the information you get is pre-evaluated. This makes you go much faster. This is an evolutionary heuristic that we have, probably since the birth of the human mind.

Follow the people who know how to treat information. Don't go yourself for the solution. Follow those who have the solution. This is a super strong drive—to learn faster. Children know very well this drive. And, of course, it can bring you to conformism and have very negative side effects, but also can make you know faster. We know faster not because there is a lot of information around, but because the information that is around is evaluated; it has a reputational label on it.

GLORIA ORIGGI is a researcher at the Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris and a journalist. She is a best-selling novelist in the Italian language, a respected philosopher in French, a cognitive scientist in English, and the person you want to sit next to at a dinner party. Her latest book, La Reputation, was recently published in France. Gloria Origgi's Edge Bio Page.

Introduction

This Edge feature is our second foray into the idea of "reputation" in the age of the Internet. The first, in December 2004, was a conversation with Karl Sigmund called "Indirect Reciprocity, Assessment Hardwiring, And Reputation," which occurred in another era (or was it another planet): no iPhones, no Facebook, no Twitter. We were sending faxes through our PCs and Macs attached to modems, and short messages through our pagers.

At that time Sigmund said, "In the early 70s, I read a famous paper by Robert Trivers, one of five he wrote as a graduate student at Harvard, in which the idea of indirect reciprocity was mentioned obliquely. He spoke of generalized altruism, where you are giving back something not to the person you owed it to but to somebody else in society. This sentence suggested the possibility that generosity may be a consideration of how altruism works in evolutionary biology."

"I am often thinking about the different ways of cooperating," he added, "and nowadays I'm mostly thinking about the strange aspects of indirect reciprocity. Right now, it turns out that economists are excited about this idea in the context of e-trading and e-commerce. In this case you also have a lot of anonymous interactions, not between the same two people but within a hugely mixed group where you are unlikely ever to meet the same person again. Here the question of trusting the other, the idea of reputation, is particularly important. Google page rankings, the reputation of eBay buyers and sellers, and Amazon reader reviews are all based on trust, and there is a lot of moral hazard inherent in these interactions."

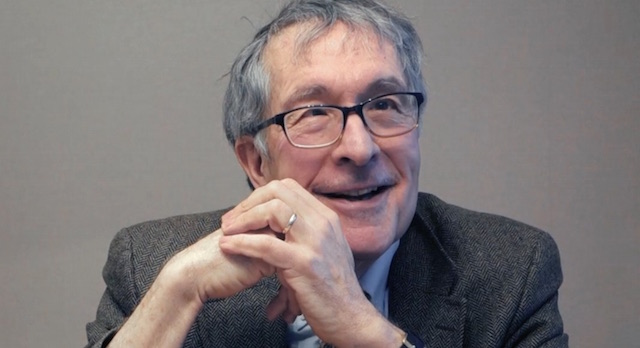

Gloria Origgi—whose previous Edge feature "Who's Afraid of the Third Culture?" appeared in these pages in 2006—is an exemplar of the Third Culture in Europe. According to philosopher Daniel C. Dennett, she has completely mastered everything from philosophy to neuroscience, moving gracefully through the conceptual jungles of everything from neuroscience to cognitive science to anthropology. A Parisian, she is an antidote to that European genre of French thought that creates the illusion of depth and profundity that Dennett calls "Eumerdification."*

In "What Is Reputation?" Origgi talks about "the double question of understanding our own biases, but also understanding the potential of using this indirect information and these indirect cues of quality of reputation in order to navigate this enormous amount of knowledge.

"What is interesting about the Internet, and especially about the Web, is that the Internet is not only an enormous reservoir of information, it is a reputational device. It means that it accumulates tons of evaluations of other people, so the information you get is pre-evaluated. This makes you go much faster. This is an evolutionary heuristic that we have, probably since the birth of the human mind.

"Follow the people who know how to treat information. Don't go yourself for the solution. Follow those who have the solution. This is a super strong drive—to learn faster. Children know very well this drive. And, of course, it can bring you to conformism and have very negative side effects, but also can make you know faster. We know faster, not because there is a lot of information around, but because the information that is around is evaluated; it has a reputational label on it."

[* Dennett writes in his book Breaking the Spell: "John Searle once told me about a conversation he had with the late Michel Foucault: 'Michel, you're so clear in conversation; why is your written work so obscure?' To which Foucault replied, 'That's because, in order to be taken seriously by French philosophers, twenty-five percent of what you write has to be impenetrable nonsense.' I have coined a term for this tactic, in honor of Foucault's candor: eumerdification."]

—John Brockman

It is going to be much more of a Wild West—what sorts of things get tried in education. The notion that we’re all going to be singing out of the same hymnal is just not going to be the case. And it may not be bad. The American federal system has been very effective in certain areas, but not in policies of higher education.

It is going to be much more of a Wild West—what sorts of things get tried in education. The notion that we’re all going to be singing out of the same hymnal is just not going to be the case. And it may not be bad. The American federal system has been very effective in certain areas, but not in policies of higher education.