Writing in Süddeutsche Zeitung, Feuilleton (arts & culture section) editor Andrian Kreye noted the following about this ongoing collaobration:

"[It] not only represents a collaboration by Brockman and Obrist’s of their own work; it is also a continuation of a movement that began in the '60s on America’s East Coast. John Cage brought together young artists and scientists for symposia and seminars to see what what would happen in the interaction of big thinkers from different fields. The resulting dialogue, which at the time seemed abstract and esoteric, can today be regarded as the forerunner to interdisciplinary science and the digital culture."

—JB

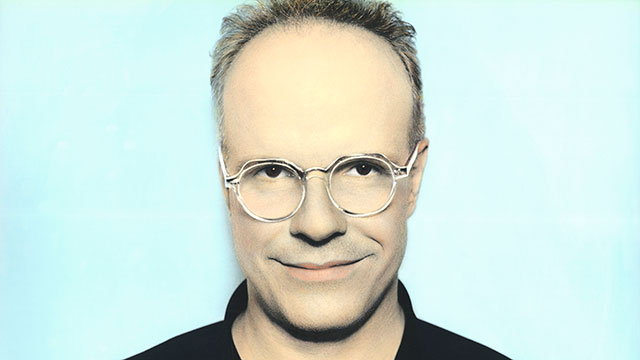

HANS ULRICH OBRIST is the co-director of the Serpentine Gallery in London. He is the editor of A Brief History of Curating, Formulas for Now and the author of several books including, Hans Ulrich Obrist: Sharp Tongues, Loose Lips, Open Eyes, Ears to the Ground, A Brief History of New Music, and Ways of Curating.

Hans Ulrich Obrist's Edge Bio Page

EXPANDED CURATION

I have always worked on public exhibitions towards the end of making the best work accessible for everyone. As Gilbert and George say, "art for all".

Ever since childhood I have been fascinated by the critical ritual of the modern era, the exhibition. The great German art historian Dorothea von Hantelmann writes wonderfully about the exhibition as a ritual. A crowd of people is not a crowd but rather a number of individuals gathered in a space who are, contra the experience of an opera or a theatrical performance, not subject to a collective control of attention.

Attention is neither monopolized nor homogenized. The exhibition is a very democratic and liberal ritual where the viewer decides the duration of his or her stay. There are, however, limits to the ritual of the exhibition. As Margaret Mead pointed out, exhibition doesn't address all the senses. Two examples are a Medieval Mass or a Bali ritual. Mead points to a lack of connection and this might explain why the average amount of time spent in front of works of art is minimal—two seconds in front of the Mona Lisa, for example.

The questions raised by Mead were brilliantly addressed by Cedric Price, the visionary English urbanist in his early 1960's Fun Palace project that I curated at this year's Venice Architecture Biennial and which is now being shown in the Swiss Pavilion.

Our goal was to develop a choreography to present the dynamic not in a frozen way but to keep it alive throughout the six month duration of the Biennale. Thus, the Swiss Pavilion becomes a hybrid between an exhibition and an event space. As Dorothea von Hantelmann summarized it: the key question of the project is how to create a ritual that is able to create ties while still remaining democratic and liberal.

We've just started another exhibition, a show in three chapters, in Arles. It's part of Maja Hoffmann's LUMA Foundation and the new institute in Arles, designed by Frank Gehry, the LUMA Parc des Ateliers. At the center of the show, which is called Solaris Chronicles, will be large-scale models of Frank Gehry's works, but then a lot of other things will happen around them. Frank has always had many connections to art, to music, to literature, to science. He's good friends with a lot of composers, and he often works with scientists. The idea was to get all of these different disciplines involved. Philippe Parreno, Liam Gillick co-curated the show, and we also invited Tino Sehgal and Asad Raza. Liam and Philippe came up with the idea that the models should be in a state of permanent movement.

We put Gehry's models on wheels together with Tino, who creates advanced new forms of choreography for exhibitions. And an exhibition always needs a soundtrack, so we asked Frank which composer he's closest to. When Julia Peyton-Jones and I did the Serpentine Pavilion with him, he wanted to work with Thomas Adès. But here he thought it would be nice to work with a composer of his own generation, with whom he'd had dialogues for many decades, and that's the great Pierre Boulez. And so the soundtrack is a work entitled "Ritual" by Pierre Boulez. It includes a light, invented by Gillick and Parreno, which throws the shadows of these moving models. It's a bit like Méliès. It's really the idea of testing an exhibition where one brings all of these competencies together. And the next stages will be in July and October, when we're going to invite artists, architects, and scientists, to add further layers to it.

It's in the French town of Arles, which is in Provence. It's where Maja Hoffmann grew up, and the new Gehry building will be the campus of her LUMA Foundation. Hoffmann invited the artists Liam Gillick and Philippe Parreno, and the curators Tom Eccles, Beatrix Ruf and myself, to form a group with her to plan an experimental art centre far from any big city, which will be designed by Frank Gehry. It's in Arles, in the marshland of France's Camargue.

Hoffmann's goal is to connect the center to ecology. So, in 2012, we took a step towards that goal by creating an exhibition called "To the Moon via the Beach", which took place in the Roman Amphitheatre of Arles. A historical site popular with the tourists and often used for bullfighting and festivals. Following an idea of Parreno and Gillick's, the amphitheatre was in transformation for the duration of the exhibition. At the start, visitors encountered an arena covered in tons of sand. This terrain was transformed from a beach to a moonscape by a team of sand sculptors and also acted as the backdrop to a series of interventions from twenty artists, who guided visitors, reacted to the shifting landscape and produced works in and around the arena.

At the end, all the sand was moved to Arles's Parc des Ateliers, a former railway construction site, where it will be accessible to the public as part of a temporary playground. It will then be re-used once again in the foundations of the forthcoming LUMA centre—a new creation, production, exhibition centre, specialising in contemporary art. As the philosopher Michel Serres says, perhaps part of today's fundamental evolution of art could be to open oneself up to living species, to open up to life and nature.

With Frank Gehry, we already have the segue in an interesting way into science, and art from architecture. What he did with scientists was to initiate interesting and important interdisciplinary conversations. And there are very few institutions or platforms where the disciplines can really meet. Obviously, you've invented Edge, this amazing possibility for all the disciplines to meet online. And in this context, when I'm making an exhibition, the question is always, how can an exhibition do that? There are museums for art, there are architecture museums and there are science museums, and the question is, how can one create platforms or situations where all these disciplines can meet?

If one looks at curatorial history, there are figures like Diaghilev, who invented his own way of doing this. He curated painting shows in the early 20th Century in Russian museums that would then tour through Europe. And then at a certain moment he felt that it was too limiting and too narrow; he wanted to go into other disciplines. But where could he go? He had to invent his own structure, which became the Ballets Russes. The Ballets Russes was like a migrating troupe, touring from city to city. And he collaborated with the greatest composers of his time like Stravinsky, and artists like Picasso. And his idea was that it would be a construct where he could pool all the knowledge and bring all the great practitioners of his time together to produce the ballet.

I think about exhibitions in a similar way. The exhibition is a great opportunity to bring it all together because it's an experimental form; it's not like a feature film, which has a prescribed duration. A film needs to be more or less 90 minutes; it's difficult for the cinemas if it's only 10 minutes or it's 12 hours. Obviously, there are experiments where filmmakers break that form, but the exhibition has this amazing advantage: that it's a ritual, it's extremely public. There isn't a prescribed time when people can visit it, or a prescribed length to their visit. They can visit it for a minute or for five hours or ten hours. There isn't the sense that one has to visit it in a group; it can very often be a one-to-one experience. But still, it's a one-to-one experience for millions of people. Within this sort of 21st Century ritual, the exhibition, there's a great opportunity to bring all the disciplines together.

One of the things that Julia Peyton-Jones and I try to do with the Serpentine Gallery Marathons, on which we've collaborated with Edge many times, is to provide a format that isn't like a normal conference: it takes place over 24 or 48 hours. And it happens in the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, so this creates a connection between art and architecture. And then one connects to all the other disciplines through the invited speakers. It's a kind of knowledge festival. The marathon is a hybrid. It's a group show, because artists are doing performances, but they're given time and not space. But it's also a conference because there are lectures and presentations. This year's Marathon, which takes place at The Serpentine Gallery the weekend of October 18-20, will be about "Extinction". It's a collaboration with Gustav Metzger, who says that we always talk about climate change, but given Hurricane Sandy in the U.S. and then what happened over the last couple of weeks here in England, where entire parts of the country were flooded, climate change just isn't a strong enough word. So he feels we need to talk about extinction. Through the topic of Extinction, we're bringing all the disciplines together, and that will lead to the Serpentine Marathon on October.

But then the question is, how can one do the same with an exhibition, where it doesn't just go on for a day or two, but for several months? The Arles exhibition will last for six months, so over this longer time period, it will need to kind of evolve. But it's carried by the same idea as the Marathons, which is this idea of going beyond the fear of pooling knowledge.

~~~

One thing that's happened since the last time we had a conversation for Edge is that I am doing less interviews and more writing This goes back to my meetings with Studs Terkel, which were a great inspiration for me. I went to see him several times in Chicago and I interviewed him. The whole idea of recording many conversations with artists, scientists and architects was very much inspired by him and by his archive of his radio shows. He had more than 10,000 hours of conversations, he told me. And he also gave me advice about how to record a conversation. But the most important thing Studs Terkel told me was that there was a moment in his life, when he met Andre Schiffrin, and all of a sudden Terkel went from just publishing interviews and doing radio shows to actually writing books.

I'd done dozens of books of conversations, and edited art books, and done sampling and collages and all kinds of catalogues, and most importantly, edited artists' books and enabled them to do books—but I'd never really written a book from scratch. So I started to spend more time every day writing, bringing together some thoughts on this subject at a moment when the word 'curating' is being increasingly used in fields outside the art world. I would call it an expanded notion of curating.

When I did my first show in my kitchen as a student in 1991, and I told my parents I wanted to become a curator, they were reassured because they were convinced I wanted to go into medicine. They thought curating had some kind of medical association! But now, that would never happen, because curating is all over the Internet. There are so many absurd uses of that expanded notion of curating on the Internet. It's a word that's completely exploding.

A recent article in the Food Section of The New York Times stated: "A museum: Chinatown feels that way at times, if you are duckling under the lintel of a basement entrance like Wo Hop's or Hop Kee's to find Cantonese crab or lobster. Sometimes the museum gets an energetic new curator like Wilson Tang, who has made the dim sum standards like char siu bao and cheong fun noodles at his family's Nom Wah Tea Parlor dance again." A clothing retailer sells a brightly coloured style of trousers called the 'curator pant', while a brand called 'CURATED' promises 'a new experience in retail design'. Then it goes on and on with music curating, and advice to business owners on curating your own business. The sociologist Mike Davis criticized Barack Obama by describing him as the "chief curator of the Bush legacy". The president of a chain of housewares says "we act as a curator, scouring the world for what we refer to as 'the best-on-planet products". Writing about his poker travails, the author Colson Whitehead reports, "I wasn't depressed, I was curating despair."

But while there are all these new uses of "curating," there's also been a lack of availability of information about where it comes from, the history of curating. And all these amazing, inspiring curators from the past have been forgotten. So the idea was to write down this history and make fragments of it available as a toolbox, not only for the art field, but, hopefully, for science, architecture, music, because obviously, in all these fields, curating exists.

~~~

I grew up in Switzerland, where Harald Szeemann was the pioneer. He was the leading European curator of his generation in the 1960s, 70s, 80s. So people often say curating started with Szeemann. But it's obviously not true, because curating has centuries of history. In the Middle Ages, processions were early forms of exhibitions. Then, of course, in the 18th Century, with the beginning of the museum, the curator was somebody who took care of the objects in a museum. Also, there's a scientific notion of curating that still exists. Then the exhibition starts to become more and more important. The curator is a maker of exhibitions, which is why in the German language one talks about Ausstellungsmacher.

If we look at such models of curating, I think we can learn a lot from them, not only for the art world but for all fields. If you think, for example, of someone like Harry Graf Kessler, who's a very early curator—an impresario, a curator, a writer, a diarist—it's an extremely interesting model of cosmopolitanism, going beyond national boundaries, and yet thinking about local differences. We can use this now in every field, and particularly in the current situation in Europe.

If we look at Félix Fénéon, the anarchist curator-writer who was very close friends with artists like Georges Seurat, you can learn a lot about the intersection of art and science. There are lots of sparks. The art historian Erwin Panofsky said, "We often invent the future with fragments from the past," and I think many of these curators can be toolboxes for the 21st Century. The medium of the exhibition is increasingly interesting for scientists, architects, designers.

~~~

I've been studying the model of Les Immateriaux. That's an exhibition that was a huge inspiration for me, and also for many of the artists of my generation, for Parreno, for Gonzalez-Foerster, for Pierre Huyghe. It's an exhibition that the Centre Pompidou mounted in 1985, which they invited the philosopher Jean-François Lyotard to curate. He had only written books, and suddenly he was invited to do an exhibition. An exhibition has a different logic from a book. He couldn't just spatialize a book. He needed to work with more dimensions; he needed to develop a different form.

He came up with this labyrinth, a maze. And that was in the mid-1980s, one of the very first shows that addressed the Internet, that addressed the digital age. It was a very early appearance of architects like Rem Koolhaus, and he also brought in scientists, he brought in designers, and he created an interdisciplinary experiment. This was a very unexpected curatorship. Then the Louvre followed up on that and did a whole series of exhibitions where they invited philosophers like Julia Kristeva or Jacques Derrida to curate shows revisiting their collection. The idea that people from disciplines who usually don't use the medium of the exhibition can use it, is a very interesting thing for the future.

Another example would be Bruno Latour, the French philosopher and historian of science. When I curated "Labratorium" in 1999 with Barbara Vanderlinden, we felt it would be interesting to do an entire city as a kind of art and science campus. We invited 50 artists and scientists to come and work in Antwerp. And we used the photography museum as a kind of headquarters, but then the show emanated out into empty buildings, into science institutes. We wanted people to visit the science labs because they're part of the invisible city, which people can't usually visit. We organized open lab days where the visitors of the exhibition could go in the afternoon and see all the labs of Antwerp.

We also wanted to get scientists and historians of science involved curatorially. So we invited Bruno Latour to curate the project with us, and he came up with this wonderful idea of tabletop experiments. He wanted to invite scientists to restage an old experiment or make a new experiment in public. It's interesting that when one moves an experiment from the scientific lab into a museum or into another lab, it won't necessarily produce the same results, and sometimes it can fail. He wanted to test that, but he also wanted to bring back old experiments by redoing them through the lens of our contemporary world and see what one could learn from them.

That's how I met the physicist and art historian Peter Galison and the art historian Caroline Jones. Latour brought in many scientists. We brought in a few artists like Panamarenko, or architects like Rem Koolhaas, to do an experiment with Latour in public, and he produced this whole series of tabletop experiments.

Latour, who'd never thought about doing exhibitions before, found this experience extremely stimulating, and then decided to move on and spend several years doing two major exhibitions in Kalsruhe. One was "Iconoclash," where he looked at destructive and constructive actions from the point of view of all disciplines, and the other was "The Parliament of Things." That's another thing that I think is interesting: these experiments in curatorial history might encourage people in other fields to go beyond books to transmit their work.

Nam June Paik, who pioneered art that used television, once told me that there's always a delay. It wasn't when television was first invented that he made his first artwork with the medium. There was a time lag between the invention of television and then Paik messing around with it and all of a sudden starting to invent a new sort of art. In a similar way, with the digital age, great digital art wasn't produced instantly, but now we clearly have generations of artists who are working with it. For example, we're working on an exhibition at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, our new space, with Ed Atkins, who grew up with the Internet.

~~~

The Serpentine now has two galleries. Julia Peyton-Jones and I invited Zaha Hadid to design the new space, bringing to life this former munitions depot, which is a restored listed building. It's old meets new. It's Zaha's new space and it's the old space brought back to life. It's the Serpentine Gallery, the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, with a bridge in between. And the digital component plays an increasingly important role in what we do. We've just launched our first digital commission with the artist Cecile B. Evans, who came up with this digital character Agnes, who lives in the Serpentine. It's an exhibition project that can only be seen online.

Marina Abramovic will be at the Serpentine Gallery from June 11th through August 25th presenting a radical new piece entitled "512 Hours", one of her transgressive and incredibly inventive performances, and she'll be in the gallery for the entire duration of the more than 512 hours of the show. There will be no objects. It will just be her and what happens between her and the people who visit. It's basically an experiment over 512 hours involving just her, her props and the visitors. And it's got to do with her very strong physical presence in the space.

During the same time period, at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, we will show a new work by Ed Atkins, one of the most prominent artists of his generation, who works primarily with High Definition video and text, exploiting and subverting the conventions of moving image and literature. Centred around an augmented and appended version of the new multi-screen video work "Ribbons", which transforms the Gallery into a submersive environment of syncopated sounds, bodies and spaces.

~~~

Can one curate on the Internet is a question I've been thinking about, not ever since Tim Berners-Lee invented the Internet in 1989, but ever since I met Bruce Sterling at the Academy for the Third Millenium. That was pre-DLD [Burda Media's "Digital Life Design" in Munich]. I received a phone call from Huburt Burda and Christa Maar saying that they had this Academy of the Third Millennium and they wanted a very young curator. I'd just started to be part of that conversation. I was 23 or 24.

I went to Munich the first conference, which was about the intersection of art and the brain. I'd never met the scientists before. Bruce Sterling was there, and he said "You have to go online." And ever since that day, I've always wondered, could one curate online? Could one do exhibitions on the Internet? And now, we're doing these digital commissions at the Serpentine, where we invite people to do digital solo shows. But I've also wondered whether we could do a group show.

Exhibitions are all about the physical interaction, about being there. There is a reason why it took so long for me to finally curate my first exhibition online: I do believe that an exhibition is the opposite of the Internet in many ways. And the reason why exhibitions are so important today is the same reason why live concerts are important again. The ritual of the exhibition is more important than ever before. It's an experience that you can't have at home in front of your computer.

Because of these considerations, it took me almost 20 years to come up with a group show that can happen online. It started, like all my projects, with a conversation with an artist, Kevin McGarry. I visited Ryan Trecartin, who's one of the most important artists of the generation. He's surrounded himself with lots of other artists, and works in these amazing constellations, moving from city to city, using houses as gathering places to develop projects.

I visited Trecartin in his house in L.A., where he's lived for the last couple of years, and we had breakfast and I had my iPhone, and he picked it up and said, "You need to be on Instagram." And he downloaded the software and then with his own phone, he took a picture of me trying out Instagram on my phone, and he posted it to all his followers on Instagram, announcing that I'd joined. It was like being thrown into the deep end and having to swim. I had to do something with it.

But for the first couple of days I didn't really know what to do. I knew for sure I didn't want to document my travels, and I didn't want to document my dinners, or lunches, or breakfasts. I needed to come up with a rule of the game. Always with exhibitions, it's about coming up with a rule of the game in conversation with artists. And then I took a photograph in Ryan's house. He has this huge calendar wall where he draws over the days that are no longer relevant because they're in the past. And then he adds new drawings; it's like a palimpsest, all hand-drawn. I took a picture of that and it was my first posting on Instagram. And then I started to post more sort of conceptual Instagrams. When I had dinner with an artist, I'd give him or her my iPhone and I'd say, "Would you make a photograph?" and then I'd post the photograph.

I went on Christmas vacation to France with the poet, Etel Adnan and the publisher Simone Fattal, her partner, who's also a great sculptor. And we'd go on walks and then we'd go to a café and have a coffee. And Etel would start to write a poem on a piece of paper. It was the most beautiful thing I'd seen in months. I suddenly became aware of the fact that what we're losing in the digital age is handwriting, because teenagers who grow up with the Internet use handwriting less and less. And then I remembered that Umberto Eco had written a piece for The Guardian a few months earlier where he lamented the disappearance of handwriting and he asked that children should be sent to calligraphy classes. I thought that rather than lamenting it, we should make handwriting attractive again. And what better way could there be to make it attractive for the 21st Century than by putting it all over the Internet?

I thought maybe that was the thing I could do on Instagram. I meet artists every day, I meet poets every day, architects, scientists. I could just ask them to handwrite a sentence or a poem or a message or a manifesto, or just a daily remark and then post it on the Internet. And that, unlike the initial idea, worked out beautifully because it just happens: the sentences are written and then we post them. And that became my first exhibition online.

I decided to also tweet it. It's interesting, because these sentences are more or less the length of a tweet, but they're obviously not written as a tweet. They're handwritten and posted as an image, so it kind of plays around with tweets in a different way. I started to do this every day and so far there have been more than 500. Little by little, it's being received outside the art world, because it is actually a movement. It's not only an exhibition, it's a movement to make handwriting present again.

A few weeks later we started our project, 89plus, at DLD in Munich, with the French curator Simon Castets. The year before, we'd done the panel "Ways Beyond the Internet," which was based on a dialogue with Karen Archey, who's written a lot on post-Internet art. I'd started to think it would be interesting to invite artists to collaborate with the technologies present at DLD and make it more interactive. So after the panel at DLD in 2013, we presented the 89plus project for the first time. The 89plus project is this idea to map the practitioners who were born in 1989 and after. 1989 was the year when Tim Berners-Lee invented the Internet, the year that GPS was invented, the year the Berlin Wall came down, the year of the protests and massacre in Tiananmen Square. Many things happened in '89 and it's the year in which the first generation who used the Internet in their early childhood were born.

The idea was to find out what that does in terms of art, literature, music, poetry, architecture, and science, and to start the dialogue with and cartography of that generation. It's obviously a long-term project. It's going to go over the next 10–20 years. We're still in our early days, but more than 5,000 people have uploaded their work on our site: artists, architects, scientists, all equally. And we look at all of this work and then curate events, lectures, panels, exhibitions out of that pool of ideas and practitioners.

After the initial DLD conference there have been different events; for example The Serpentine 89plus Marathon in London and, the Jumex 89plus event in Mexico, and artist residencies. We believe that it's important in terms of creating a platform for this new generation. The residencies, where we bring the different practitioners together, are maybe the most important aspect. There's this idea for a residency on a boat. Agnes B has this boat, Tara, which captures ecological data about climate change all over the world. The idea is to have an artist in residence whenever the boat goes on a trip, so that the artist and the scientists could interact in terms of the climate discussion and the environmental discussion. That, I would say, is an unusual residency.

There are now three young emerging 89-plus artists in residency at the Google Cultural Institute in Paris, creating that bridge. This idea of the artist placement came from John Latham and Barbara Stevini, who believed that one shouldn't disconnect art from society. He thought there should always be an artist in residence in many non art world related contexts. In some way, this connects to our experiments in art and technology, leading to a clearer idea of how artists and technology can be teamed up. It's very early days, but we hope that there are going to be many, many more contexts opening up in the world of technology where we can bring artists together with all these other practitioners.

For me, it's very important to do these grants and residencies, because when I was 22 or 23, just after my "Kitchen Show," I got a residency from The Cartier Foundation, which at that time was in Jouy-en-Josas, on the outskirts of Paris, and it's an interesting model for how an institution works. They had these little houses on a campus, and they'd invite artists to be in-residency curators, and then connect them to fashion, music, and literature.

It was an important experience of my life. I was in Switzerland, and all of a sudden I could leave, I could travel! I'd always traveled on night trains but I could never go away for long, because I had no money for hotels. Now, for the first time, I could leave Switzerland for longer. And my neighbors were Huang Yong Ping, the Chinese artist, and Absalon, the artist from Israel, who developed architectural living models. Huang Young Ping completely changed my way of working, because he made me aware of only looking at Western art. Exhibitions such as "Cities on the Move," which I curated with Hou Hanru, emerged from that residency. It was a life-changing experience.