A CULTURAL HISTORY OF PHYSICS [1]

THE FOREWORD

By Charles Simonyi [2]

AN EXCEPTIONAL BOOK SUCH AS THIS could have been created only under exceptional circumstances. My father was a working physicist and a beloved university professor who taught a whole generation of Hungarian electrical engineers. His textbooks on the foundations of electrical engineering have been translated into many languages. Yet, in the politically charged atmosphere of the 1960s in Hungary, his quasi-apolitical personal conduct, based on the age-old virtues of hard work, good character, and charity, was interpreted as political defiance that could not be countenanced by the state. Hence, he progressively lost his directorship at the Physics Research Institute, his post as department head, and finally his teaching position altogether. I was still a minor when I left the country—and my parents—in search of a better life. It was understood by all that my doing so—a political act in a totalitarian era—would make my father’s situation even more difficult.

Besides being a scientist, my father was a great humanist, not only in terms of his concern for his fellow man but also in the sense of a scholar of the humanities: he was extremely well read in the classics as well as in contemporary literature and history. The break in his career at midlife did not drive him to despair; his humanism instead commanded him to work on the subject he had perhaps always wanted to work on: the history of the interplay of science and the humanities. His first notes became a lecture series, first given off campus, in the evenings at the invitation of student organizations. Much later, when I was able to return to Hungary, I was privileged to listen to one of these lectures, still filled to more than capacity with students and young intellectuals, hearing my father convey the excitement and wonder of scientific development—how difficult it was to make progress in science, not simply because of ignorance but because the arguments were complex and the evidence was often ambiguous, and how the scientists gained courage or were otherwise influenced by the humanities. The success of these lectures gave rise to the present book that he continued to revise and extend almost until his death in 2001.

All history books that treat the modern period face a problem: when should the discussion close? My father prided himself on keeping the book up-to-date as it progressed through five Hungarian editions and three German editions. Now, nearly a decade after his death, we edited the story down to what was firmly settled by the year 2000, and asked the noted and brilliant physicist Ed Witten to write an epilogue bringing us up to date with the current scientific outlook, as opposed to the already stale speculations made in the recent past. ... [continue [3]]

CHARLES SIMONYI [2], software engineer, computer scientist, entrepreneur, and philanthropist, is Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton; Chairman, CTO and Founder of Intentional Software Corporation; Former Director of Application Development, Chief Architect, and Distinguished Engineer at Microsoft Corporation (1981-2002), where he led development of Microsoft Excel, and Microsoft Word, some of Microsoft's most profitable products; Creator of Bravo, the first WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) word processor while at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (1972-1980).

Examples from the excerpt [3]: Click on images to enlarge ...

Figure 3.9 The Book De recolutionibus orbium coelestium (Nuremberg, 1543)

Figure 0.12 The balance and the harp

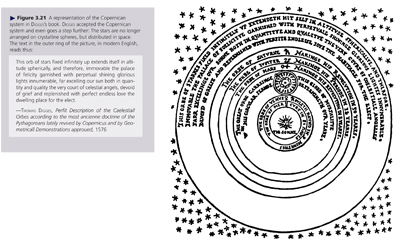

Figure 3.21: A representation of the Copernican system in Digges's book

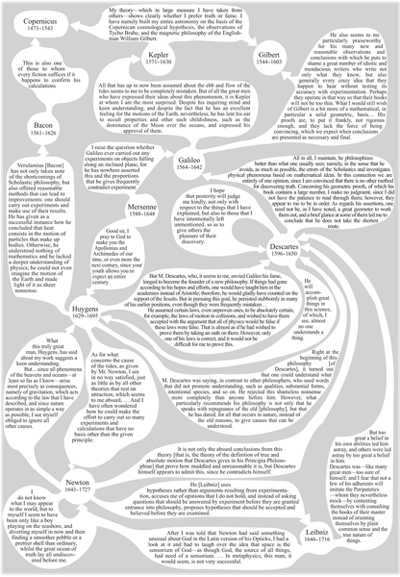

Table 3.4: How the great figures of the seventeenth century judged one another