SOCIAL NETWORKS AND HAPPINESS

Happiness is a fundamental object of human existence. To the extent that it is synonymous with pleasure, it could even be said to be one of the "two sovereign masters" that, Jeremy Bentham argued, govern our lives. The other master, lest we forget, is pain.

Our happiness is determined by a complex set of voluntary and involuntary factors, ranging from our genes to our health to our wealth. Alas, one determinant of our own happiness that has not received the attention it deserves is the happiness of others. Yet we know that emotions can spread over short periods of time from person to person, in a process known as "emotional contagion." If someone smiles at you, it is instinctive to smile back. If your partner or roommate is depressed, it is common for you to become depressed.

But might emotions spread more widely than this in social networks—from person to person to person, and beyond? Might an individual's location within a social network influence their future happiness? And might social network processes—by a diverse set of mechanisms—influence happiness not just fleetingly, but also over longer periods of time?

We recently published a paper in the British Medical Journal that addressed these questions. We studied 4,739 people followed from 1983 to 2003 as part of the famous Framingham Heart Study. These individuals were embedded in a larger network of 12,067 people; they had an average of 11 connections to others in the social network (including to friends, family, co-workers, and neighbors); and their happiness was assessed every few years using a standard measure.

We found that social networks have clusters of happy and unhappy people within them that reach out to three degrees of separation. A person's happiness is related to the happiness of their friends, their friends' friends, and their friends' friends' friends—that is, to people well beyond their social horizon. We found that happy people tend to be located in the center of their social networks and to be located in large clusters of other happy people. And we found that each additional happy friend increases a person's probability of being happy by about 9%. For comparison, having an extra $5,000 in income (in 1984 dollars) increased the probability of being happy by about 2%.

Happiness, in short, is not merely a function of personal experience, but also is a property of groups. Emotions are a collective phenomenon.

To follow up this study, we have also been examining online social networks. Emotional clustering and contagion are so fundamentally rooted in our ancient evolutionary psychology that—we believe—they should carry over to the very modern online world of email, blogs, and social networking sites like MySpace and Facebook.

One of our efforts has involved the examination of a group of 1,700 college students who are interconnected in Facebook. We examined these students' online profiles. We noted who their friends were and we also studied their photographs.

The photographs were valuable in two ways. First, we coded who appeared in photographs with whom. People who take the trouble to be in the same place, take a photograph together, upload the photograph, and label ("tag") it, almost certainly have a closer relationship with one another than the usual "friends" people indicate in online social networking sites. In fact, while the average student in our data had over 110 friends on Facebook, they had an average of only six "picture friends" (i.e., people close enough that they tagged the student).

Second, we coded whether the students were smiling in their profile photographs, and we mapped the network of students and their picture friends, making note of who was smiling and who was not. In a way, this is the online analogue of the research we did with happiness in the Framingham social network, though smiling is, of course, different than happiness.

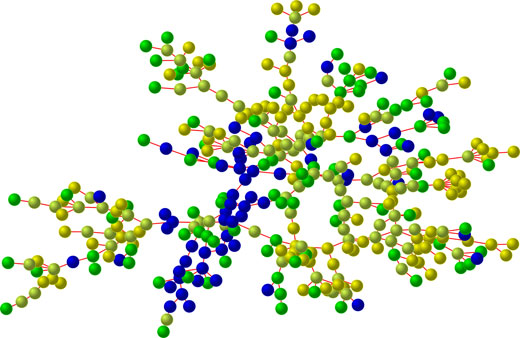

The figure below is a map of part of this Facebook network in 2007. It contains 353 students, each represented by a node; each line between two nodes indicates that the connected individuals were tagged in a photo together. Students who are smiling (and who are immediately surrounded by smiling people in their network) are colored yellow. Students who are frowning (and who are immediately surrounded by such serious looks) are colored blue. Shades of green indicate a mix of smiling and non-smiling friends.

Notice how strongly the blue nodes and the yellow nodes cluster together, indicating large-scale structure of smiling in the online network. Moreover, people who do not smile seem to be located more peripherally in the network. In fact, statistical analysis of the network shows that people who smile tend to have more friends (smiling gets you an average of one extra friend, which is pretty good considering that people only have about six close friends). Not only that, but the statistical analyses confirm that those who smile are measurably more central to the network compared to those who do not smile. That is, if you smile, you are less likely to be on the periphery of the online world.

It thus seems to be the case, online as well as offline, that when you smile, the world smiles with you.

[click on image to enlarge]

"Smiling in an Online Networks of College Students"

|